Frederick Cook As Physician

The Young Doctor’s Wanderlust

In 1887, Cook entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, later transferring to New York University. While balancing the grueling schedule of being a medical student and supporting himself with a milk delivery business, he met and married Libby Forbes in 1889. Libby and Frederick were expecting their first child around the time that Cook sat for his medical exams. Tragically, due to complications of the pregnancy, their baby was born dead, and Libby died a week later in June 1890. Throughout his youth, he had always dealt with hardships and struggled. This last blow was devastating.

Once he had passed his medical exams, Cook sold his portion of the milk delivery business to his brother Theodore and opened a medical office in Manhattan. The practice was slow to take off. He did not have many patients. Shattered by the loss of his young family, the young doctor was not unduly concerned about his practice and dreamed of a life of adventure. Elisha Kent Kane, the arctic explorer who was lionized by the The New York Herald for having survived a succession of brutal winters encased in arctic ice was his beau ideal. Kane, too, was a physician. It was Kane’s life of action and subsequent acclaim that greatly appealed to him.

In the early spring of 1891, Cook saw a short newspaper article, datelined Philadelphia, that would change his life forever. He was to write,

“One morning there appeared in the New York Herald the news announcement that Lieutenant R.E. Peary was organizing an expedition to explore the unknown Northern Limits of Greenland. I promptly wrote Peary, offering my services…” 1

A Thoroughly Decent Fellow

According to Canadian author Pierre Berton, it was impossible not to like Frederick Cook. “He belonged to that human subspecies whose members seem forever courteous, gentle and apparently open.” Even Robert E. Peary called Cook “a thoroughly decent fellow”. 2 before their friendship evolved into the bitter acrimony that was to hurt them both in the next century. To all, Cook was genial, inventive, eager to help out and always optimistic. Despite the character flaws that were to reveal themselves in the controversies that surrounded him later in life, he was always a good doctor. Frederick A. Cook proved that many times on all of his hazardous polar journeys. Even the indigenous people he befriended came to see him as a man with special gifts, if not a shaman.

Cook as Physician on the Peary North Greenland Expedition

The two men, Cook and Peary, had high regard for each other throughout most of the 1891 – 1894 expedition. Cook saved Peary’s leg after it had been fractured horribly in a freakish shipboard accident shortly after their arrival in Melville Bay, Greenland. Peary valued the young physician’s skills and ingenuity in the face of emergencies. For his part, Cook praised Peary’s courage and forbearance in the face of adversity in all the time they spent together.

The time Cook spent with the Inuit in North Greenland was a life-changing experience for the doctor. Not only did he learn igloo building, dog handling and other survival basics, he learned the language and embraced the customs of the Greenland Inuit. He had been hired by Peary to serve the expedition as physician, photographer and ethnologist. Ethnology, as a scientific discipline, was in its infancy at the time. Cook was never to forget an Inuit elder named Sipsu who was to offer him his mystical insights into the cause of the northern lights and raise his appreciation of the life-sustaining power of the sun. It was on this first polar journey that Cook learned a lot about the effects of prolonged darkness on the physical and mental health of human beings. It was knowledge that he was to apply to good effect on the Belgian Expedition of 1897-1899.

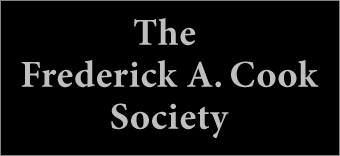

Dr. Cook’s Lifesaving Medical Care on the Belgian Expedition (1897 – 1899)

It was on the Belgian expedition that Cook’s medical talents and polar experience came to the forefront. Not long after the Belgica entered Antarctic waters, Cook began to to earn the gratitude and affection of all the men on board. In their isolation and after their harrowing near shipwreck in Tierra del Fuego (see details), it was a comfort to the men just to have someone care about them and pay close attention to them. He was determined to keep them from falling into debilitating states of depression, knowing as he did what long polar nights and isolation had in store for them.

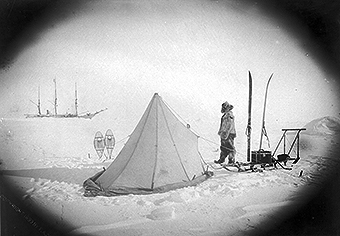

Like Roald Amundsen, Cook was always working on improving equipment and transportation methods. Seen here is the wind resistant tent he designed.

Shortly before the start of the long Antarctic night, Cook noticed disturbing changes in his companions’ behavior. Melancholy and dread filled the air. Daylight became shorter until the last dim glow of sundown on May 16, 1897. For the next seventy days, sunlight was to be a memory and the perpetual darkness would drive the men to despair and lethargy. Besides the punishing conditions, the thought of being trapped in the ice for the foreseeable future. The death of Emile Danco, a dear shipmate to all and close friend of the commander, made them wonder “who among us will come after him?”

Cook became a close friend of the first mate Roald Amundsen, who dreamed of being a world-famous polar explorer since his childhood in Norway. In December 14, 1911, Amundsen was to become the first man in history to reach the South Pole and return (see details). On this expedition, he approached the Belgica’s dire circumstances as training and rose to the challenge. In the darkness, he explored, exercised, designed and improved equipment and planned other expeditions. Cook, likewise, kept active. His obligations as a physician demanded activity and by nature he was not one to settle into a routine of inactivity, even if he was confined to a cave, tent or an icebound ship. Cook and Amundsen often explored the frozen surroundings together, facing numerous perils that deepened their respect for one another.

In the Peary Expedition to North Greenland (1891 – 1892) Cook experienced punishing bitter cold and months long darkness for the first time. He knew their physical and psychological effects. On the Belgica, he took it upon himself to keep everyone’s spirits up and their minds occupied. In late March, Cook interviewed every man on the ship at length, officers and crew, to identify the sources of growing discontent which visibly manifest themselves as the ship became increasingly icebound and at the mercy of ocean currents. The ship was always in danger of being crushed by ice. The commander, Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery, had even begun to question his own decision to winter in Antarctic waters – doubts that he kept to himself – while the crew increasingly resented his bad judgement in the matter.

Dr. Cook Recognizes Seasonal Affective Disorder

The sun filled months indicated here are misleading. Most days in Antarctica are misty, foggy and gray. Bright sunshine is rare. For definitions of civil, nautical and astronomical twilight click here or on chart.

S.A.D. or “Seasonal Affective Disorder” as it came to be known, was formally recognized as a form of winter depression in 1984. The term was first used in a paper by Norman Rosenthal and colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, MD. Dr. Cook identified the disorder in 1899 and called it “polar anemia”. He suspected that the stress due to confinement, isolation, boredom and fear contributed to the phenomenon. But he believed that the most critical factor was the disappearance of the sun.

“Oh, for that heavenly ball of fire! Not for the heat – the human economy can regulate that – but for the light – the hope of life.” He remembered the observations of Sipsu, 3 the Inuit elder who knew full well the powers of the sun as both a life source and a celestial talisman.

In a 1894 article he wrote The New York Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics he said “I should judge from this that the presence of the sun is as essential to animal as it is to vegetable life”. After his time in North Greenland, he would never be convinced otherwise.

To Cook’s way of thinking, the weakness, pallor, irregular heartbeats and mental atrophy of the men were akin to the etiolation of plants deprived of sunlight. On the Belgian Expedition, he ordered the most severely affected men to stand naked in the glow of blazing wood or coal fire, “the best substitute” for the blazing sun. He called it “The Baking Treatment” and was the first known instance of light therapy that is used today to treat seasonal affective disorder. The men showed marked improvement in very short time. However, it was not enough to reverse the damage of the Antarctic night and an even more serious affliction. 4

Besides The Baking Treatment, the doctor prescribed an hour a day’s walking exercise. Those who could stand were commanded to trudge around the perimeter of the icebound ship in what came to be called “The Madhouse Promenade“. The sardonic name reflected the dire circumstances the men found themselves in. Although these directives had a measurable positive effect on the men, they were not enough. For one thing, during the hour-long loops men began to freeze parts of their faces, fingers and feet without realizing it. At first, Cook attributed the blunting of the men’s senses to “enfeebled circulation“. Then he began to suspect a more serious ailment. 5 The name for it was “scurvy”.

Scurvy Makes Its Grim Appearance

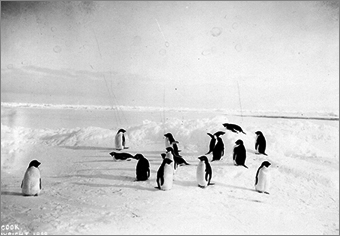

Until the Antarctic night set in, flocks of penguins were easy to find. The birds’ absence of fear when confronted by humans made them easy to hunt. Along with seals, they were hunted for the food source they might supply in dire circumstances. The only problem was, the taste of penguin meat was vile to most sailor’s palates.

The unmistakable signs of scurvy among the crew members included lethargy, weakness, discolored waxen skin, along with a buildup of liquid under the eyes called “dropsical effusion”. If untreated, it would progress to excruciatingly painful loosened joints, collapsed blood vessels, gangrene, and inevitable death by a cerebral hemmorhage or heart attack. It was the single greatest killer of sailors in the Age of Sail, from the days of Columbus up to the Age of Steam when steamships lessened the hazard by shortening the length of sea voyages. By the turn of the twentieth century scurvy was thought to have been eradicated by crew’s diets of antiscorbutics in the form of citrus fruits like limes and lemons or sauerkraut. Vitamin C, which enables the body to efficiently use carbohydrates, fats, and protein, was not discovered until the 1930s by Albert Szent-Györgyi (see details). Polar voyages, which often involved years of isolation, were not accounted for.

Cook, of course, did not know about Vitamin C.. But he did say that “scurvy had a thousand remedies which, in itself, is the best evidence that it is not understood“. However, it was not lost on him that the Inuit never suffered from scurvy. Their diets consisted mainly of raw meat and fat. Their diets were rich in Vitamin C, despite the absence of citrus fruits. Cook learned this valuable lesson in North Greenland.

Whatever fresh fruit that might have been purchased in Tierra del Fuego would have gone bad by winter. The ascorbic acid in the lime juice that de Gerlache had bought in Europe would have oxidized in the bottling process. The canned food that formed the basis of the men’s diet didn’t contain any vitamin C. As the crew’s condition deteriorated, the doctor became convinced that fresh meat would be their salvation.

Commandant de Gerlache disagreed. He insisted that he had provided the expedition with adequate supplies of antiscorbutics. The Belgica’s crew had hunted penguins and seals before winter set in, but the bagged game was set aside and frozen, preserved for only the direst circumstances. “The British Navy has used lime juice against scurvy for fifty years,” de Gerlach huffed. “What is good for them is good for us.”

The commandant’s resistance to eating penguin meat set an example for the crew. Everyone but “The Last Viking”, as he came to be called, was adverse to following the doctor’s orders. The stoic Amundsen ate the penguin raw and was quick to recover. Despite his example, his shipmates still refused to eat penguin meat, disgusted as they were by its smell, taste and texture. The argument over the adverse effects of canned food persisted until the proof was in the eating. Amundsen and Cook saw to it that ample supplies of seal tenderloin and penguin breasts would be on hand when the time came. That time came very quickly.

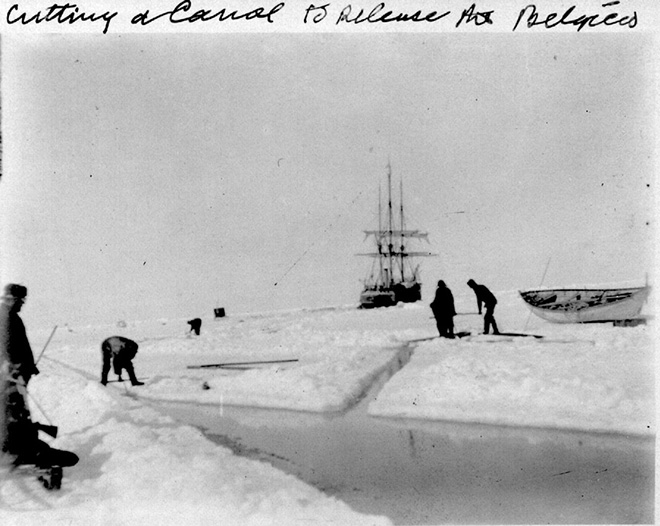

To free the Belgica from the ice in the brief Antarctic spring, Cook proposed an asymmetrical approach to sawing the ice. The 700 ft. effort was often a frustrating enterprise. But the exercise did wonders for the men, as did the exposure to fresh air and sunlight. Eventually, the ice battered ship was freed.

Those who followed listened to Cook and ate daily servings of penguin saw their symptoms improve. Those who followed de Gerlache’s example deteriorated. The biggest uncertainty of all onboard was who would be the next victim.

On July 14, 1897 Captain George Lacointe appeared to be the most likely to die of scurvy. Commandant de Gerache wouldn’t be far behind. The captain was losing the use of his arms and legs. His pulse was weak and his heart rate high. Shockingly pale and cold, he said to Cook, “death is creeping up to me from my feet.” He drifted off to sleep.

By no means a cure all for all the the men’s afflictions, Cook’s regimen was this: Nothing was to be consumed “except milk, cranberry sauce, and fresh meat, either penguin or seal steaks fried in oleomargarine.” He called for the baking treatment, light daily exercise and no alcohol.

*Note:

Tachycardia (tak-ih-KAHR-dee-uh) is the medical term for a heart rate over 100 beats a minute. Many types of irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias) can cause tachycardia. A fast heart rate isn’t always a concern. For instance, the heart rate typically rises during exercise or as a response to stress.

North Greenland Expedition (1891 – 1894) | Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897 – 1899) | Erik Relief Expedition (1898) | Mt. McKinley Expeditions (1903 and 1906)

Aftermath 0f Mt. McKinley Expeditions | North Pole Expedition

References:

1 Sancton, Julian. Madhouse at the End of the Earth: New York, Crown/Random House LLC, 2021

2 Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail; The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole 1818 – 1909. Toronto, Ontario 1988. pgs. 586-587

3 Sancton, Julian. Madhouse at the End of the Earth: New York, Crown/Random House LLC, 2021 pgs. 140 – 141

4 Sancton, Julian. Madhouse at the End of the Earth: New York, Crown/Random House LLC, 2021 pg. 185

5 Sancton, Julian. Madhouse at the End of the Earth: New York, Crown/Random House LLC, 2021 pgs. 185 – 187

6 Sancton, Julian. Madhouse at the End of the Earth: New York, Crown/Random House LLC, 2021 pg. 197

© The Frederick Cook Society | 2022

Sullivan County Museum

265 Main Street, Hurleyville, NY 12747

Mailing Address:

P.O. Box 27. Hurleyville, NY 12747

FACpolar@frederickcookpolar.org

Site design by Roger Dowd Design