Introduction

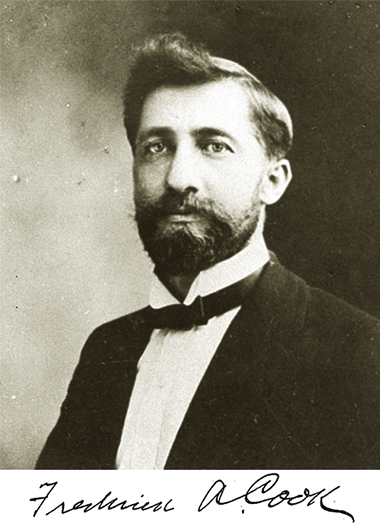

In 1996, the Frederick A. Cook Society Collection was donated to the The Byrd Polar Research Center at The Ohio State University. Contained within the collection is documentation of the life of Dr. Frederick Albert Cook (1865-1940).1 The following biography was kindly provided by Laura Kissel, Polar Curator, The Ohio State University. http://go.osu.edu/frederickcook

Frederick Albert Cook was born on June 10, 1865 in Hortonville, NY, the fifth of six children born to Theodor and Magdalena Koch (later changed to Cook). When Frederick was only 5, his father, a physician, died of pneumonia, leaving the family impoverished. Growing up poor, Frederick held various odd jobs while attending school. The family eventually moved to the Brooklyn area, where Frederick graduated from grammar school.

Financial constraints kept him from going immediately to high school, and he began a printing business to raise money, while going to school at night. He also decided to follow in his father’s footsteps and go to medical school. In order to raise the tuition money, he sold his printing business and joined ranks with his brother Theodore to start a milk delivery business, which was very successful.

COOK’S EXPEDITIONS

North Greenland Expedition

(1891 – 1894)

Belgian Antarctic Expedition

(1897 – 1899)

In 1887, Cook entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, later transferring to New York University. He continued to support himself with the milk delivery business. Despite the grueling schedule of medical student and entrepreneur, he met and married Libby Forbes in 1889. Libby and Frederick were expecting their first child around the time that Cook sat for his medical exams Tragically, due to complications of the pregnancy, his baby was born dead, and his wife died a week later, in June 1890.

Soon after, Frederick found out he had passed his medical exams. He sold his portion of the milk delivery business to Theodore and opened a medical office in Manhattan. But business was slow to take off, and he did not have many patients.

“One morning there appeared in the New York Herald the news announcement that Lieutenant R.E. Peary was organizing an expedition to explore the unknown Northern Limits of Greenland. I promptly wrote Peary, offering my services…” 2 And thus, Dr. Cook’s life would forever be changed.

Further reading: A Hero For Our Times By Allegra Rosenberg • New York Times • 2023

North Greenland Expedition (1891-1892)

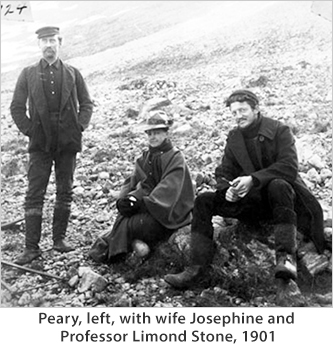

In 1891, Dr. Cook volunteered for Robert E. Peary’s expedition to North Greenland, serving in the role of surgeon, ethnologist and photographer. The goal of the expedition was to discover the northernmost extent of Greenland. Peary’s underlying quest, however, was fame. The press covered his plans for the expedition extensively and many men sent their applications. A total of seven members were taken for the wintering party, including the controversial decision to take Peary’s wife, Josephine, who would serve as cook and dietician. The party departed from Brooklyn, NY on 6 June 1891 in the sealer Kite. Cook would make a good first impression on Peary, for Peary would break his leg in a freak accident just prior to the Kite reaching Whale Sound. The expedition would continue anyway, with Dr. Cook and other members of the expedition sent out to hunt and make contact with the Inuit. See Cook’s photographs of the Inuit of North Greenland and other indigenous people.

All members of the expedition, including Peary, were unprepared for the difficulty of life in the frigid conditions of Greenland. According to Dr. Cook’s memoir, “we went through the first Arctic night with the usual half insane mentality of novices. In our stupid stages of unpreparedness, we lived as brothers with the savages. As the twilight of the long night returned, we were equipped for the task at hand…. Peary’s sublime courage saved the day. In returning, all resolved never to venture into the Arctic again.” 3

Of course, this statement proved to be untrue, as Cook would venture into the cold regions of the Arctic and Antarctic numerous times over the course of his exploring career. In 1893 and 1894, Cook organized his own expeditions to Greenland, “…in which the main purpose was to offer facilities to college professors and students for a vacation of study and research in the little known Arctic…” 4

Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897-1899)

Returning to his medical practice in Brooklyn after concluding his expeditions to Greenland in 1893 and 1894, Dr. Cook continued to read about polar exploration. In late August of 1897, a chance reading of the New York Sun reported that the Belgian Antarctic Expedition was ready to leave Antwerp, but had been delayed due to the resignation of the expedition physician. Cook quickly cabled his willingness to go. Within hours he received the instruction to meet the group at Rio de Janeiro. 5

“At last I am on the way to the land which has been the dream of my life – the mysterious Antarctic.” 6

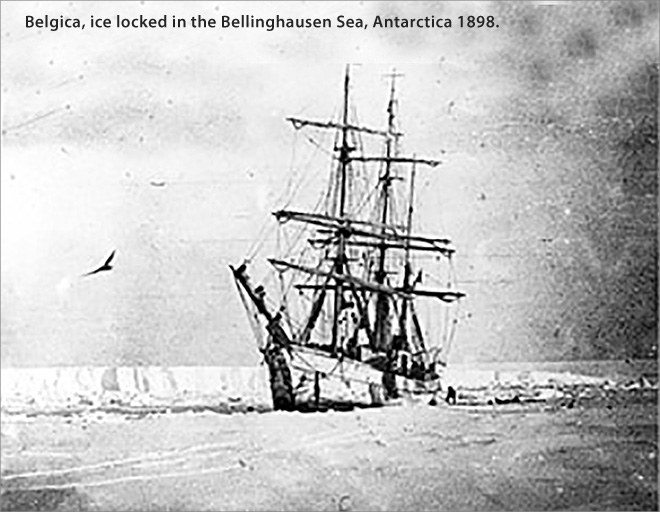

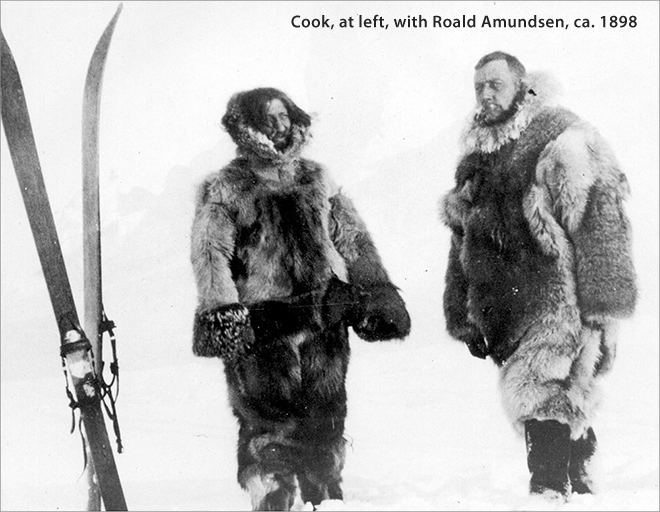

The expedition crew was international in scope, including members from Belgium, Norway, Russia, Romania, and America. The commander was Adrien de Gerlache of Belgium. It was during this expedition Cook would meet Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Amundsen remained a stalwart supporter of Cook throughout all of the controversies that overshadowed Cook’s later life. The ship Belgica did not reach Antarctic waters until January 20, 1898, late in the exploring season. Between January 23 and February 12, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition made 20 separate landings on the islands that filled the strait that de Gerlache named “Belgica Strait.” Later, it was renamed the “Gerlache Strait,” and is considered his greatest geographical discovery. View maps of the region.

“Late in February we entered the main body of the sea ice…after penetrating 90 miles we found ourselves firmly beset.” 7

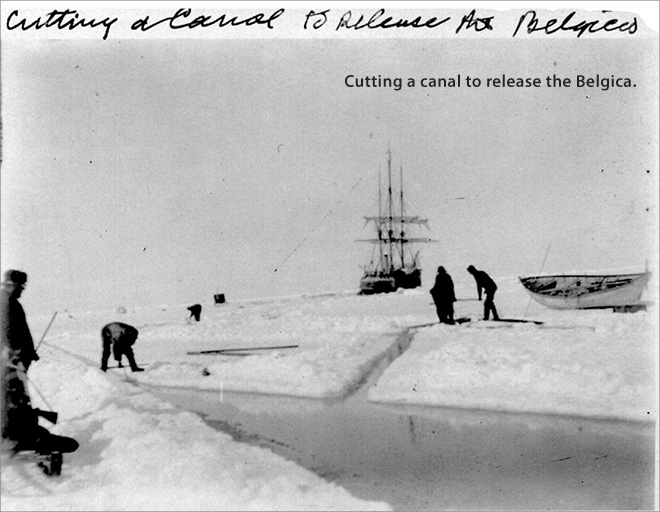

The crew was unable to extricate the ship from the pack ice and spent the next thirteen months drifting with the ice. Although efforts were made to free the ship, they were not sufficient. The multinational party would be the first to undergo the rigors of the long Antarctic night.

On May 17, 1898, the darkness of the winter night closed in. Within a few short days, the crew became irritable; they were perpetually cold, damp and crowded together, struggling to communicate. Cook’s services as a medical doctor were now very much in demand. Recognizing the signs of scurvy in the men, Dr. Cook recommended that they eat fresh seal meat. Wintering below the Antarctic Circle, the crew was forced to endure two months of unbroken darkness, more than a year of snow and hail, deafening winds, illness and insanity.

On May 17, 1898, the darkness of the winter night closed in. Within a few short days, the crew became irritable; they were perpetually cold, damp and crowded together, struggling to communicate. Cook’s services as a medical doctor were now very much in demand. Recognizing the signs of scurvy in the men, Dr. Cook recommended that they eat fresh seal meat. Wintering below the Antarctic Circle, the crew was forced to endure two months of unbroken darkness, more than a year of snow and hail, deafening winds, illness and insanity.

In June of 1898, Dr. Cook took moral control of the ship. Recognizing the need to take their minds off their plight, he organized card games, including betting (which of course would never be honored). Despite his best efforts, time passed and the crew became more and more desperate. There was talk of abandoning the ship and attempting to escape across the ice. But in which direction? Finally, on December 31, a stretch of open water appeared 700 yards ahead. It was Dr. Cook who recommended that they saw and blast a channel. The work was difficult. The explorers battled for a month, working day and night. At last, on February 15, 1899, the ice began to move and the channel was opened. The engine was started, and for the first time since March 2, 1898, the Belgica moved under her own propulsion. Finally, on March 14, 1899, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition emerged from the pack ice.

Dr. Cook would return from this expedition as a hero.

Erik Relief Expedition (1898)

“Peary had now been engaged in promoting Arctic expeditions for ten years. He had spent perhaps a million dollars. To himself in prospect and in retrospect, his life was now a failure. This was evident in the aging effect of his failing physique and in the icy mentality which now replaced a former youthful alertness.” 8

“Peary had now been engaged in promoting Arctic expeditions for ten years. He had spent perhaps a million dollars. To himself in prospect and in retrospect, his life was now a failure. This was evident in the aging effect of his failing physique and in the icy mentality which now replaced a former youthful alertness.” 8

Peary had gone north once again in 1898. The goal this time was to reach the North Pole from Greenland. Unfortunately, the timing was all wrong – the ship that he would take, Windward, would need to be fitted with new engines in order to have enough power to force its way north. Though Peary managed to find a backer to pay for the work, the necessary labor was delayed by a strike, and Peary ventured north without the needed modifications to the ship.

Additionally, Peary was forced to winter much further south than he had planned, on Cape D’Urville. Always the fierce competitor, a meeting with Otto Sverdrup, whose expedition was wintering close by, fueled Peary’s will to push north to Fort Conger. The darkness of the winter night, combined with the extreme temperatures – at times more than 50 degrees below zero – made finding Fort Conger extremely difficult. Peary’s health suffered, and he had to have seven of his toes amputated due to frostbite.9

Meanwhile, Peary had been gone more than two years, and his sponsors had become concerned about his welfare. Cook was asked to join the Erik, a steamer sent north to find Peary and his expedition. Cook describes the trip north to locate Peary as ‘uneventful’, and Peary was found on board his ship Windward in Etah Harbor, with his wife Jo and daughter Marie. Peary and his physician Dr. Dedrick had had some kind of falling out, with both claiming that the other was crazy.

According to Cook’s memoir, “Those of us on the Eric (sic) felt that the Arctic had done something to the mentality of both… not insanity, but the effect of long continued use of devitalized food.”10

Though urged by Dr. Cook and Josephine to end the expedition and go home to get some much needed rest and recuperation, Peary refused. Not yet ready to give up hope for reaching the North Pole, he sent the Erik back to civilization, with Dr. Cook on board.

North Greenland Expedition (1891 – 1894) | Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897 – 1899) | Erik Relief Expedition (1898) | Mt. McKinley Expeditions (1903 and 1906)

Aftermath 0f Mt. McKinley Expeditions | North Pole Expedition

References:

1Dr. Cook’s unpublished autobiography is entitled Hell is a Cold Place. A copy can be found in the Frederick A. Cook Society Collection, The Ohio State University Archives, Box 9, folders 38-45.

2 Hell is a Cold Place: ch. 1, page 9

3 Hell is a Cold Place: ch. 2.1, page 4.

4 Hell is a Cold Place: ch. 2.1, page 7.

5 Hell is a Cold Place: ch. 5, page 7.

6 Cook, Frederick A. Through the first Antarctic night, 1898-1899; a narrative of the voyage of the “Belgica” among newly discovered lands and over an unknown sea about the South Pole, ch. 1, page 3. This is the first sentence of the book.

7 Ibid, introduction p. xxi. Erik Relief Expedition (1898)

8 Hell is a Cold Place, ch. 5 page 8

9 Mills, William J. Exploring Polar Frontiers: a historical encyclopedia, 2003. Entry for Peary, Robert, pp. 512-513.

10 Hell is a Cold Place, ch. 5 page 8

© The Frederick Cook Society | 2026

Sullivan County Museum

265 Main Street, Hurleyville, NY 12747

Mailing Address:

P.O. Box 27. Hurleyville, NY 12747

FACpolar@frederickcookpolar.org

Site design by Roger Dowd Design